AN UNPREDICTABLE PATH TO A PREDICTABLE OUTCOME

By Frank Graves

This article was published in partnership with the Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP). Full article available here.

[Ottawa – January 11, 2016] The 42nd federal election was a unique and historically important election. The public judgement expressed in this election reveals some clear features of our changing society. And by exploring the true meaning and significance of this election, we hope to highlight how these results point to a broader and fairly significant redirection of Canadian society as a whole.

To do so, we need to weave this analysis into a story that captures the rhythms, movements, and forces resulting in the surprising return of the Liberals from a decade in the political wilderness to a majority victory. The real meaning of the election only becomes clear when set in the broader context of the aftermath of another surprising majority, that of May 2011. Many have written on this topic already but we approach it slightly differently: through the lens of the Canadian citizenry.

Our evidential base is unusually strong. Using three separate probability based survey platforms, we conducted over 130 thousand interviews in the period from January to the election and about that many again in the period from the last election until the beginning of this year. We have an unparalleled inventory of tracking and diagnostic measures that allows us to unpack this election in ways that are not possible elsewhere.

The tale of this election can, we suggest, be seen as a four-act play. The postscript – the next four years – is of course unwritten. But we argue that a real understanding of the outcome of the election can only be possible within the broader context of the past four years.

We suggest that the seeds of this dramatic return to a progressive government were sown in the prologue to what we have called a four-part morality play (focused as it is on values or moral sentiments). The final results of this election reflect a vigourous public judgement rooted in the growing normative tension between Harper Conservatism and the dominant values of a progressive majority. It also reflects a rising discomfort with the withering of middle class progress and a rejection of the neo-liberal model of minimal government, austerity, and trickle-down economics. We believe that this result is revealing of how Canadian society is evolving and that the lessons of this period have broader implications for the prospects for progressive politics in other settings. We would argue that this result shows one public solution to the paradox of an increasingly progressive citizenry being held hostage to the shrinking conservative values of an aging minority. Or put another way, we can ask why do progressives win all of the key culture wars yet have much less success in winning the political wars?

We begin with a prologue to the play.

Prologue: a Big Shift?

The prologue begins on the night of May 2nd, 2011 when Stephen Harper achieved the strong, stable majority he was seeking with an almost identical share of popular vote as Justin Trudeau received on the 19th of October. This astonishing result baffled the pollsters and dispirited the progressive majority of Canada alike. By an eerily similar 39.6 per cent (versus the Liberals’ 39.5 per cent four years later), the Conservatives had secured a majority that seemed shocking in light of a clear disconnect with the expressed values and interests of most Canadians. The paradox of a minority-majority was further reinforced by the fact that only 24 per cent of all Canadian voters provided what was to become a mandate characterized by an absolutist approach to power for Stephen Harper.

This result was also fashioned from the extremely uneven turnout across generational lines. The increasingly smaller youth voter segment had voted at nearly half the rate it did in 1993 and they had not been favourable to the incumbent. The influence of a burgeoning senior cohort who continued to vote in very high rates – along with the tepid turnout in younger and progressive Canada – was the key to this majority. Some argued that we were seeing the installation of a sclerotic gerontocracy fashioned on the exaggerated and imagined fears of older Canada.

A more optimistic scenario was that offered by Darryl Bricker and John Ibbitson that this was part of a ‘Big Shift’ that would see the Conservative party replacing the Liberal party as the new natural governing party of Canada. Their thesis was indeed much broader than this, but in our analysis we offer something of a correction, suggesting that these tectonic shifts were perhaps more apparent than real and that a return to Liberal majority is a reflection of a deeper values contest. Indeed, rather than a large-scale cultural or demographic shift, these election results represent the end of a detour that took until 2015 to undo. While there were several conservative governments in place at the time that Stephen Harper attained his majority, the vast majority of senior governments in Canada today are currently progressive governments.

The final election outcome was highly uncertain but the majority of the electorate were determined to do two things; retire Mr. Harper and to install a clearly progressive government. This impulse was rooted in what we can call a public judgement that rested on reflection and values – we borrow the idea by way of the sociologist Daniel Yankelovich.

Act I: A descent into darkness for progressive Canada

The opening act shows the impacts of the Harper majority on the Canadian public. It didn’t take very long at all after the results of May 2011 to see acute buyer’s remorse emerging in response to a Harper government that now took majority control of the federal government. And it revealed the increasing incommensurability of the two Canadas that now occupied the country. The roughly one-third of citizens that favoured the Conservatives had a very distinct profile in terms of both demography and values. Conservative Canada was older, more likely to be male, less educated, and was focused to the west of the Ottawa River. They fared relatively better in the economy and were far more attracted to the fiscal and social values of Harper conservatism than the rest of the country.

Progressive Canada was decidedly unhappy with the trajectory of the country and the federal government. Barometers of trust, approval, and confidence in national direction plumbed new lows – and would do so throughout this period. This clearly documented democratic malaise was exacerbated by a growing sense that the economy wasn’t working the way it had in the past and that the shared prosperity that underpinned the healthy growth of the last half of the twentieth century was being replaced by an ill-defined sense that we were moving collectively towards an ‘end of progress.’ The middle class bargain, a social contract upon which Canadians built a modern, postwar society seemed to be broken. Even the moderately more favourable post-2008 performance of the Canadian economy gave way to renewed stagnation and pessimism.

Moreover, the early rhetorical flourishes of the Harper government – that had signalled a hard right approach to government – were now translated to more definitive policy decisions. The federal state was diminished (to just 13.5 per cent of GDP) and the key policy directions of the Harper government were increasingly at odds with the values of the majority of citizens. Whether it was a ‘tough on crime’ approach, the shuttering of research and abandonment of evidence-based decision making, or a much more militaristic foreign policy with an unblinking pro-Israel stance, collectively these positions were increasingly disconnected from what the majority still considered the core values and the public interest.

Act II: A crimson tide rising and a neo-Trudeauvian ascendance

In the era of the permanent campaign, politics is always salient but this reached new intensity with the Harper government. With the entry of Liberal leader Justin Trudeau, there was a major shakeup in the political landscape of Canada. There had been lots of fluidity in the Canadian electorate since Stephen Harper assumed power, but most of this mobility was the slow movements of progressive voters seeking an antidote to the protracted period of Conservative rule.

In the 2011 election, more small-l liberals voted NDP than Liberal and many Liberal voters stayed home. The emergence of another Trudeau seemed to initiate a new movement in this slow dance of the promiscuous voter. It seemed a year after assuming power that Justin Trudeau was on an unstoppable path to victory forged from his focus on middle class renewal and a more optimistic and progressive agenda. Indeed, in a piece we released exactly one year ahead of the 2015 election, we found the Liberals in almost precisely the same position that they found themselves on election night in October (38.5 per cent, compared to their Election Day showing of 39.5 per cent).

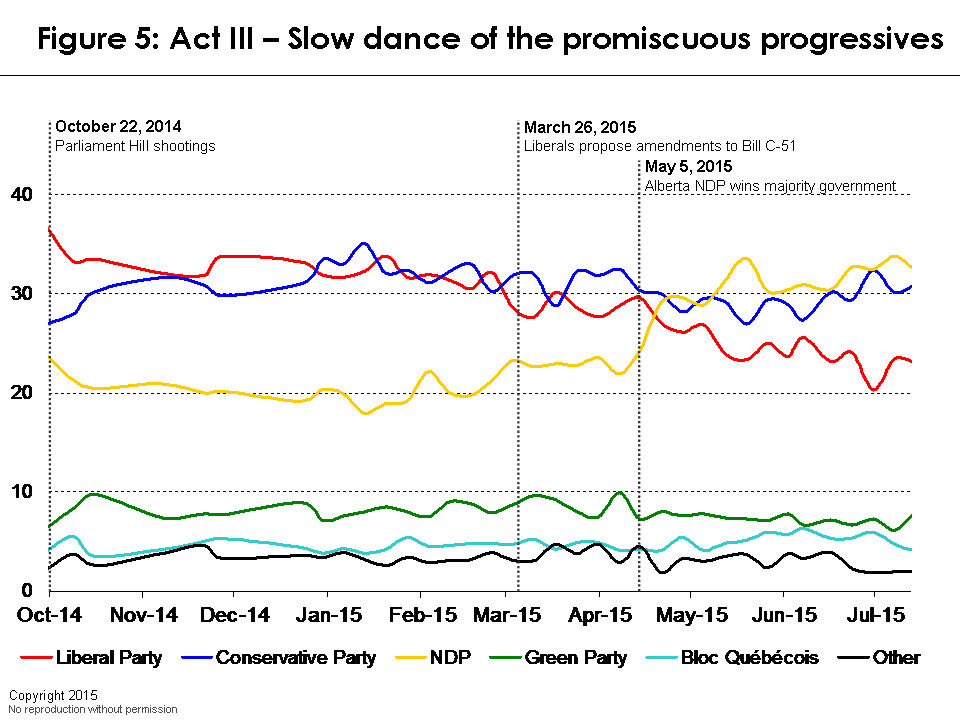

The path to Liberal victory was, however, not to be a smooth and uninterrupted march to power. In Act III, the pre-campaign period, we see all kinds of permutations with the Conservatives strengthening, the NDP re-establishing their ownership of the progressive segment, and the Liberals slowly but seemingly surely sliding into political oblivion. These new shifts begin, however, with a very specific set of events.

Act III: The slow dance of the promiscuous progressives: “change partners again”

But then, events, dear boy.

As Harold Macmillan famously noted, political events can transform a campaign and, in the fall of 2014, they did just that. The shooting on the Hill – and the tragic attack in a parking lot in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu – reignited concerns with security and terror. Prime Minister Harper shrewdly exploited these concerns for example, in his declaration that Islamic Jihadism had become the greatest immediate threat to Canada.

And as these events saw Stephen Harper rise in the polls and approval ratings, Justin Trudeau began to sink slowly but surely. This was abetted by his decision to support C-51, which put wind in the sails of Tom Mulcair and the NDP. And in this newly salient context of national security and terrorism, the clear movement of university-educated Canada from the Liberals to the NDP was undoubtedly linked to this position. The shocking installation of an NDP majority in Canada’s most conservative province in May 2015 added further momentum to the federal party. Between the October shootings and the May 2015 election of the provincial NDP in Alberta, the Liberals dropped from a significant 12-point lead to third place in a three-way tie.

In contrast, the movement for the NDP during this period was entirely in the opposite direction and the party would remain in the lead in the polls until the longest campaign since 1872 was well underway. Act III saw the recovery of Stephen Harper and the NDP and Liberals exchanging places as the most likely champion of the promiscuous progressives.

The net result of this pre-campaign period was an outlook on October 19th that was as clear as mud.

Act IV: The 78-day campaign: Unprecedented dynamics and a whiplash-like shift from the opening positions

This was a highly unusual and important election. Consider the beginning of the campaign. In what had been a tight three-way race, the NDP now found itself in first place with the Conservative Party sandwiched between them and the suddenly-trailing Liberal Party. In the last six elections, the Liberals have never improved their position on Election Day from their position in the polls at the commencement of the campaign and, in four of those six campaigns, they actually fell backward. Peter Newman’s gloomy prognosis for the death of the Liberal Party had become suddenly more plausible.

The first month of the campaign featured little attention by the voters but there was growing attention paid to the Duffy affair, which seemed to have a real but ephemeral effect on Stephen Harper’s prospects. It may have been that the long campaign wasn’t simply about maximizing the financial advantage of the much larger Conservative coffers. Placing the Duffy circus well before voting day would give sufficient time to erase any corrosive impacts of this affair on the Conservative Party and in hindsight that is exactly what happened. While the movements were modest, the Liberals showed significant, but gentle, upward movement over the month and the NDP showed moderate decline.

There was an early debate and Justin Trudeau showed up (with pants no less). From our polling, it appears that Justin Trudeau’s debate performances were a modest factor in his comeback. By corollary, Tom Mulcair with a frozen smile reminiscent of Jack Nicholson in the Shining didn’t seem to help his cause much. Overall, however, not much else seemed to be happening, as a reluctant electorate were more preoccupied with barbeques than stump speeches. But once again, as August drew to a close, events intervened. Two events coalesced in short order that would profoundly alter the course of the election.

Two game-changers

The first occurrence was the opposite decisions by Tom Mulcair and Justin Trudeau on the issue of balanced budgets. Shortly after Tom Mulcair announced his commitment to balanced budgets, Justin Trudeau took the vividly different position of borrowing to support major investments to stimulate the economy. These two policy stances marked a clear turning point in Liberal and NDP fortunes.

The second event was the effects of the tragic picture of a drowned Syrian child; this was probably the point that demarcated the shift from an important election about the economy to an historic election about Canadian values. The short-term benefits to the Conservative Party from this and the related culture war around the niqab were eventually eclipsed and shifted the election to a broader contest about foundational values. Harper may have had the high ground on the specific public opinion around the niqab and citizenship ceremonies but he was emphatically in the inferior position when the debate widened to a vision contest about which values would define Canada in the future. Let’s turn back to the fateful contradictory positions taken by Tom Mulcair and Justin Trudeau on balanced budget.

If Trudeau’s position a year earlier to support C-51 had vaulted Tom Mulcair into the lead as the champion of promiscuous progressives, then their starkly different positions on the balanced budget issue had an even more profound and permanent effect. In one of the most dramatic political stumbles in Canadian history, Tom Mulcair went from knocking on the door of 24 Sussex to being reduced to the leader of a diminished third party. Nothing was more instrumental in this fall from electoral grace than the decision to commit to balanced budgets.

While these opposed positions cast Mulcair and Trudeau as Horwath and Wynne in a national reprise of the 2014 Ontario election, the final outcome of this election was also shaped by the events and campaign strategies following the Syrian refugee crisis. This crisis began with the searing image of the drowned three-year-old, Alan Kurdi, on the front pages of Canadian newspapers.

The initial impacts were both baffling and depressing to progressive Canada. After an initial consensus that Stephen Harper had committed a fatal error in his hard-hearted treatment of this issue, something became surprisingly clear in our tracking. The Conservative Party started to grow support and raise the engagement levels of their constituency. Many of the lapsed Conservative voters from 2011 who had been sitting in the undecided camp returned to the fold. Our results at the time (September 2nd to 8th) suggested a rise in Conservative fortunes and, as we noted at the time, signalled the possibility of another Conservative government for the first time.

So while events intervened once more to shift the parties’ electoral fortunes, it was this deeper reshaping of the electoral context that ultimately defined the closing stages of the election campaign.

Values and emotional engagement define the campaign

There were other factors at play but none was more important than the role of values and emotional engagement. The voters clearly told us this and the rhythm and shifts of voters in the campaign revealed this. As evidence, we note that voters told us this election had very large stakes both for them personally but also for the country. This was reflected in high levels of expressed emotional engagement (something missing in 2011 from center-left voters) and this in turn was expressed in real behaviour. Nearly three million missing voters from the last election showed up this time. Most of these voted Liberal.

“Overall turnout will be higher than in 2011 and the higher the overall turnout, the poorer the prospects for Stephen Harper.”

-EKOS Research Associates, October 17th, 2015

The two exhibits below demonstrate just how salient values were in shaping the outcome of this election and how the emotional engagement advantage had shifted to progressive voters (who were more discouraged in 2011). It was the values contest that produced these unusually high levels of emotional engagement.

While Stephen Harper enjoyed the high ground on the narrow question of whether women should be allowed to wear a niqab at a citizenship ceremony, he was in a decisively inferior position on the broader values questions that ensued. Clearly, Canadians favoured a progressive vision for Canada in its preferred foreign policy orientation as well as the broader question of the proper role of the state and its public institutions.

And when we asked Canadians to consider the significance of the coming election – specifically in value terms – they responded clearly. This election was an important declaration of self-identification, and whether in their determination to remove a 10 year regime, or more abstractly as a vote to define collective values, this election meant something to Canadians.

The sequential dynamics of an unusually fluid campaign

As if the tensions between balanced budgets versus deficits on the one hand and the resonant concern for Canadian values on the other weren’t enough to sharpen the mind of the electorate, this election also featured a late shift with progressive voters uniting under the Liberal banner in the last week of the campaign.

We often hear of apocryphal late shifts to explain polling mistakes. But in this election there were larger late shifts in the campaign and several of the pollsters caught this movement. It is also clearly revealed in our post-election survey completed immediately following the election.

There have been different accounts about the degree to which there was a late shift. In fact, some of the mid-week polls, which showed something close to the final outcome, would have to be inaccurate at that time if a late shift occurred. Most of the probability-based polls (both IVR and live interviewer) showed a significant late shift and that was very clearly evident in our late polling as well. Moreover, the post-election survey confirms that a very sizable fraction of voters changed their vote in the last week or even on Election Day.

As the chart below reveals, the electorate’s movements were far more dynamic in this campaign than in 2011 with a significantly lower number of voters who made up their minds before the campaign (43 per cent in 2015, down from 56 per cent in 2011).

We wonder who these late shifters were – and as we have just suggested – this election featured far more movement than we saw in 2011. The vast majority of these shifts ended up favouring the Liberals and there were also some modest but important defections from the Conservative ranks – notably some late change of mind by seniors. While we have long tracked the support of older Canadians for the Conservative Party, that support crumbled in 2015. Senior support for the Liberals nearly doubled between 2011 and 2015 (while senior support for the Conservatives declined in the late stages) – our first hint perhaps that the intergenerational divide between older Canada and ‘Next Canada’ may be healing.

Another critical factor in the progressive success and in the progressive solution voters found was in the university-educated vote. Perhaps sick of the more acute values clash between university educated and conservative Canada, this large and growing voter segment were critical to the outcome of the election. Consider this the revenge of the latte-sipping elites who were sick of being pilloried by the anti-intellectualism pervasive in the Harper regime.

And when we look more carefully at the broader population, we see that it was indeed the group of promiscuous progressive voters (which included a large representation of university educated and under-50 Canada) that fed into the Liberals’ success. The next chart details the effects of this group that as we have shown, swung between progressive options during the last few years, and that finally made their choice for now-Prime Minster Trudeau. The final majority was a multi-factor result, but clearly depended on the huge swing of promiscuous progressive voters to the Liberals. The Liberals ultimately outstripped each of their opponents by a margin of approximately three-to-one.

And if we look carefully at where these switchers went, it was from among the ranks of those originally leaning to the NDP that the Liberals made their greatest gains. The critical groups are the second and third in the figure below, which show the overwhelming advantage that the Liberals had in attracting Conservative and, even more so, NDP defectors. Anecdotally, it is also interesting that the Green Party that the Green Party showed a similar haemorrhage to the Liberals, which may explain why our late polls showed the Liberals too low and the Greens too high by almost the exact amount of these late shifters.

The Liberal victory was built on a solid cascade of returning and new voters throughout the campaign. The strongest growth occurred during the period from early September to October and was linked to the factors mentioned earlier. But it was the late last week shift that ensured the victory that ensured the victory and propelled them from minority to majority.

Quebec

In Quebec, we saw a distinctly different election than in the rest of the country. In the early stages of the campaign, Quebeckers appeared less engaged and, for a long time, the province appeared to be on route to reproducing the NDP’s success of 2011. It then entered a highly unsettled period with a Niqab debate that saw a short-term boost to Conservative fortunes. This advantage quickly faded however, perhaps mirroring Pauline Marois’ secular charter gambit in the 2014 provincial election.

From the outset of the campaign, the Liberals had a lot of trouble getting political traction in Quebec, but started showing signs of life in the mid stages of the campaign, although they were hurt by the Gagnier affair. The late movements were more dramatic and important in Quebec than anywhere else. The Liberals were ultimately able to siphon votes from all three of their competitors.

Quebeckers decided late in the campaign that more seats for the Liberals was a better bet to hasten Mr. Harper’s exit. There is some evidence that this late shift continued right through to the ballot box and was largely at the expense of the NDP.

New Canadians

New Canadians actually decided to vote Liberal late in the campaign. This was particularly critical in the restoration of Liberal Party dominance in the 905 and other areas surrounding the GTA. While the new Canadian vote may indeed be somewhat more socially conservative, they too found the extremes of barbaric practices hotlines and Bill C-24 crossed the boundaries of Canadian sensibility.

Ground game also mattered

In 2011, the Conservative won their majority on the strength of their vastly superior turnout in comparison to other parties. Part of this was lower emotional engagement on the part of the centre-left parties, but it was also a reflection of superior get-out-the-vote, which was linked to a better ground game. The Conservatives had a more sophisticated voter identification system (CIMS), which was linked to better get-out-the-vote and also most likely linked to vote suppression activities.

The Liberals learned from these activities and invested heavily in much more sophisticated ground game for this election. Nearly 100,000 volunteers were deployed and their activities were targeted based on a sophisticated voter identification system influenced by the successful Obama campaigns.

The chart below strongly suggests that contacts from the Liberal Party were quite effective in switching voters to the Liberal Party. While other factors may have been at play, it is quite possible that this ground game was a factor that propelled the Liberals into majority territory.

Polls may have had more of an impact on macro strategic voting than in any previous election

Riding-specific initiatives designed to support ‘strategic voting’ may have been ineffectual and caught in the problem of a dramatic amount of late movement. It is the case, however, that this election may have seen a more direct causal relationship between the polls and late shifting than we have seen in any previous election. Note the strong positive correlation between influence of the polls and late decision making.

Youth turnout

Our data suggest that the increased 2015 turnout reflected, at least in part, a greater participation by younger voters than in recent elections. Whereas voters over 50 constituted a majority (54%) of those casting ballots in 2011, the surveys suggests the 2015 numbers will show a rough parity between voters over and under 50 in 2015.

Our data also suggest that the Liberal Party was a clear winner among all age groups, giving the current party a broad-based support with respect to age, combining the effects of both greater youth turnout and the shift back to the Liberals among older voters. This stands in sharp contrast to the previous government’s strong support among older voters and lack of support among younger voters.

Impact of cellphones

In 2011, sampling cellphone-only households increased our prediction error. The cellphone-only population was much larger this time than in 2011. They were also much more emotionally engaged and they moved late and decisively to the Liberals. This was another ingredient of the multi-factored explanation of the final majority. As we predicted in an iPolitics article in the final week of the campaign, the cellphone-only segment of the population was critical to the outcome of the election: ‘If they show up, Harper loses; if they don’t, he wins.’

They showed up.

Final act (with a postscript on an unknown future)

The night of October 19th saw a remarkable recovery on the part of progressive Canada, and the culmination of what appears to have been only a temporary ‘Big Shift’ to a new conservative order. In hindsight, the result appears to be an almost inevitable restoration of progressive Canada.

The impressive political success of the Harper government was built on an unremitting focus on politics and tactics. But even the swollen war chests, the carpet-bombing of the airwaves with both Government of Canada and political advertisements, the targeted boutique tax goodies for desirable voter segments, the invoking of xenophobic race-baiting and demagoguery in the pursuit of power, none of these were powerful enough to withstand the force of an awakened progressive majority who declared they had simply had enough. In the end, it was these very culture war tactics – which had a temporarily positive impact on Harper’s prospects – that ultimately opened up a values-based vision war that tilted the scales decisively in Justin Trudeau’s favour. As we have seen, an important election about the economy was transformed into an historic election about values. This victory reveals the priority of values-driven public judgement over retail politics and dark ops.

If the 2011 election was all about inertia and retaining advantage, in 2015 it was all about movement. In the most dynamic and engaged election in a generation, the electorate came to a collective judgment that reflected a commitment to restoring a progressive, tolerant and open Canada. The values advantage was also bolstered by a more authentic economic narrative – that progress has halted and that middle class decline needs to be treated promptly and vigorously. And somewhere at the cusp of values and interests lay a clear judgment about the role of the federal state and public institutions.

The tired bumper-sticker simplicity of ‘lower taxes and less government equals prosperity for all’ had unravelled to the point where it has become a cruel hoax. The neoliberal agenda of trickle-down economics and austerity that had been central to Harper’s plan to reconstruct Canada in the lineage of Thatcher and Reagan was cast aside decisively. Recall that Seymour Martin Lipsett had noted that one of the enduring value differences separating Americans and Canadians was how each country responds to ‘statism’ and collectivism.

It was on this critical misunderstanding of progressive Canada where Tom Mulcair made his fatal error of endorsing a balanced budget. Justin Trudeau seized on this and used it to open a huge gulf between the Liberal Party and the front-running NDP. If the lessons from the Ontario election weren’t clear enough, recent polling has clearly shown that the broad swath of progressive voters put a much lower priority on balanced budgets than stimulating growth and cushioning citizens from the fallout of a stagnant economy. At best, Mulcair made the notion somewhat less objectionable to Conservative voters who weren’t ultimately going to vote for him.

This election result is reminiscent of Rachel Notley’s historic victory in that it also resulted from a ‘traffic-light coalition’ of progressive voters. In this case, however, the coalition favoured the Liberals and not the NDP. Notley did not make the error of a focus of balanced budgets, but rather ran on a clear progressive platform. In an interestingly similarity, both Trudeau and Notley leapt from sub-opposition to clear majority governments. In both cases, the clear trend was towards a progressive option, but not necessarily towards a specific party.

As the curtain closes on this campaign, we are left to ponder what this means for the future of Canada. Citizens told us they saw this as a uniquely important election and our post-election polling confirms almost extravagant expectations for the new government. Having gathered more than 200,000 cases over the last year, we feel very confident in having accurately measured the pulse of the Canadian public. Indeed it has been a story governed by the ebb and flow of their worries and desires for a renewed direction for the country.

We do see a government which has, at least temporarily, erased the deepening generational and social class fault lines that were fracturing the country. Two things are very clear at this early stage. This will be a very different government than the one that held power for the last nine years. Secondly, this government has strongly committed itself to the restoration of progressive Canada and this appears to reflect a much stronger connection to the core values of our society at this time.

Lessons for progressive democracy

The renewed success of progressive politics in Canada may reflect a harbinger of broader trends occurring in the advanced Western world. It may also have implications for our neighbours to the south as they approach a new presidential election. As the Trudeau team clearly benefitted from the lessons from the Obama team, it’s only fair to offer up some broad advice based on this important progressive success story.

Role of values as emotional triggers

The keys to victory for the progressive movement were transforming the election into an election about values, which are emotionally engaging. Progressive parties have lagged behind the parties of the right in terms of understanding the emotional power of values. Progressive voters in Canada were sick of winning the culture wars and losing the political battles. This reflected a lack of understanding by progressives of just how emotionally resonant a strong values narrative can be. As we know, there is nothing more instrumental to political success than emotional engagement. For the first time since 2000, the Liberal Party spoke passionately and clearly about Liberal values.

Importance of not trying to mimic neo-liberalism / fiscal rectitude

Understanding at this point, after years of stagnation, the lower taxes/less government mantra has worn thin and progressive governments are succeeding by focusing on active government, not minimal government. The bumper sticker simplicity of ‘lower taxes and less government’ has been laid bare as a cruel hoax. Consistently, progressive government that run on a platform of active government and strong public institutions are beating conservative governments running on trickle-down economics and austerity. It really is about restarting middle class progress and this is seen as a more plausible solution by contemporary voters.

Methodology

This study was conducted using High Definition Interactive Voice Response (HD-IVR™) technology, which allows respondents to enter their preferences by punching the keypad on their phone, rather than telling them to an operator. In an effort to reduce the coverage bias of landline only RDD, we created a dual landline/cell phone RDD sampling frame for this research. As a result, we are able to reach those with a landline and cell phone, as well as cell phone only households and landline only households.

The field dates for this survey are October 20-23, 2015. In total, a random sample of 1,973 Canadian adults aged 18 and over responded to the survey. The margin of error associated with the total sample is +/-2.2 percentage points, 19 times out of 20.

Please note that the margin of error increases when the results are sub-divided (i.e., error margins for sub-groups such as region, sex, age, education). All the data have been statistically weighted by age, gender, region, and educational attainment to ensure the sample’s composition reflects that of the actual population of Canada according to Census data.

Click here for the full report: The Reinstatement of Progressive Canada (January 11, 2016)

Please undertake a deeper analysis of voter behaviour by age groups. The huge increase in support for the Liberals could be a function of much younger voters turning out in significantly higher numbers. Your over/under 50 age break doesn’t shed nearly enough light on this important hypothesis.